Pittsburgh seems to rack up “most affordable” and “most livable” rankings the way Meryl Streep racks up Oscar nods. However, the city is rapidly becoming less affordable in terms of housing costs. Rents are rising faster than renters’ income. New developments are outside most Pittsburgh residents’ price range. And the city has fewer income-restricted apartments than people who need them.

Since becoming mayor, Bill Peduto has put affordable housing on the list of his priorities and recently introduced a series of executive orders urging public and private entities to make progress on the issue. City leaders are looking for ways to put money and accountability behind the initiatives.

Here is an explanation of the state of affordable housing in Pittsburgh:

How is housing in Pittsburgh becoming less affordable?

In the summer of 2015, LG Realty Advisors issued notices to the residents of the Penn Plaza Apartment complex to get out in 90 days. Since 1966, the 312-unit East Liberty complex that LG Realty owns had offered below-market rents — provisions legally enshrined in ownership of the property because the city completed construction using funds from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). Residents had been paying $400 to $800 a month. A few years after that covenant expired, new luxury apartments and chain stores began encroaching on the neighborhood. LG Realty wanted to bulldoze to build a complex anchored by higher-end residences and a Whole Foods. The result has been an uproar over gentrification and a protracted legal conflict with the city.

The Penn Plaza development has been a symbol of a trend, where units well within the price range of low-income Pittsburgh residents are being squeezed out of the market and replaced by new, swanky places aimed at high-earners.

In 2015, the Pittsburgh City Council and Peduto established an Affordable Housing Task Force, which commissioned the consulting firm Mullin & Lonergan Associates to complete a needs assessment of city housing.

“We didn’t have any policies in place,” said Peduto’s chief of staff, Kevin Acklin. “We always had enough de-facto affordable housing.” But surges in new development caused the administration to think the market was changing and the firm had several concerning findings.

Median gross monthly rent (rent plus utilities) was $500 for Pittsburgh in 2000, compared to $794 in 2014. That’s $116 more than it would be if inflation were the only factor.

Median gross monthly rents in Pittsburgh

The portion of the rental market consisting of units costing less than $500 a month has diminished considerably. And rentals costing more than $1,000 grew almost sixfold.

One might chalk this up to the existing market being augmented by ritzy new buildings in hot neighborhoods, like Lawrenceville and Shadyside. That’s not the case. The rental market is not growing.

And, the average rent for a newly built one-bedroom apartment averaged $1,599 in 2015.

Meanwhile, the incomes of renters, a population that typically earns less than homeowners, have not risen at all.

Median incomes for renters in Pittsburgh

Conversion of renters into homeownership within the city does not explain the trend. The number of owner-occupied houses has decreased since 2000.

Also, the value, and hence cost, of houses is rising. The real estate website Zillow forecasts that values will continue to climb.

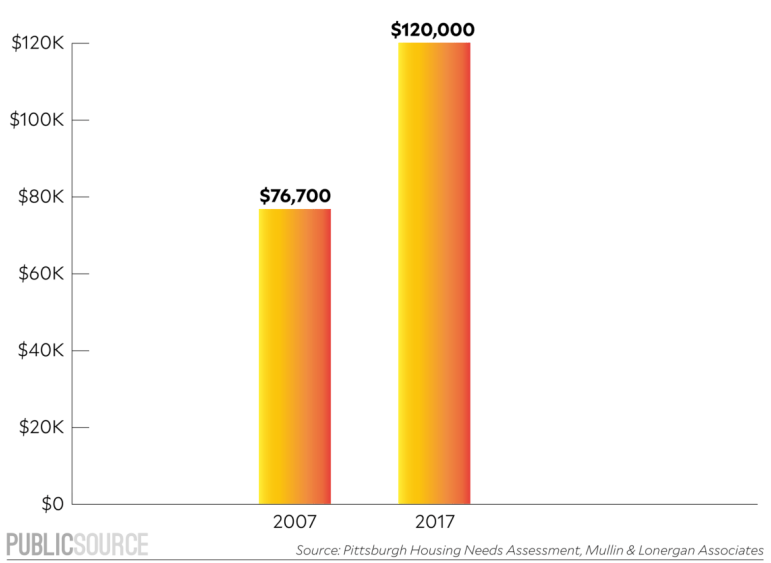

Average house prices in Pittsburgh

What is “affordable” for Pittsburgh?

Affordability, of course, depends on one’s resources. “Someone who makes $12,000 [a year] is going to have more trouble affording housing than someone making $20,000,” said Ira Mabel, a housing and community development specialist at Mullin & Lonergan Associates. “It’s important to keep several brackets in mind when considering what is ‘affordable.’”

There are guidelines to who may need housing assistance. The federal government provides $8 billion worth of tax credits to develop subsidized housing nationally. It also provides the Section 8 vouchers to help tenants pay for non-subsidized housing. This means the federal government defines what is “affordable” for the sake of receiving those benefits.

The overall stance is that those who pay more than 30 percent of their income for housing are “cost-burdened” and may have trouble paying for other necessities, like food, clothing and medicine. According to Mullin & Lonergan Associates’ needs assessment, about a third of Pittsburgh households are cost-burdened.

Different federal funded programs are meant to assist those in different income brackets. Some are available to anyone with a “low” income, which is up to 80 percent of an area’s median income. Other benefits go specifically to “very low” earners, who make up to 50 percent of the median income, or “extremely low” earners which is determined by a multifaceted equation. In Allegheny County, the cap for people who may be eligible for federal assistance are: individuals making $39,900, families of two making $45,600 and three-person households making $51,300.

While there is no exact rent scale for “affordable” housing in Pittsburgh, subsidized units rent for between $400 and $800 a month, depending on location and size of the apartment, Mabel said.

How many income-restricted rental units are in Pittsburgh?

The needs assessment found that 15,809 of the city’s residential units — about 10 percent of the total — are restricted to renters who have low income levels. Since the May 2016 report, about 290 units have been demolished, Mabel said.

The report also found the city needs another 17,241 cost-controlled units to provide for all households earning 50 percent of the area’s median household income or less.

Graphic: 17,241 dots to help you better grasp Pittsburgh’s affordable housing problem

In addition to the people in units reserved for those of lower incomes, about 6,000 Pittsburgh residents have Section 8 benefits to help them pay for housing on the unsubsidized market.

How is subsidized housing funded?

About a quarter of the city’s subsidized units are funded or owned by the city. According to Mabel, the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh owns and operates 2,767 units and funds another 1,204 under private management. Most are for elderly people.

After the 1960s, most cities ceased building, managing and maintaining ownership of public housing complexes. Instead, the federal government began incentivizing private developers to construct buildings with an agreement to keep some or all units affordable to people earning a fraction of an area’s median income. “That got really popular in the ’80s and ’90s,” Mabel said. Some firms specialize in building affordable housing through these incentives.

In many cases, federal benefits, most importantly Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, are funneled through state agencies and combined with other funds.

“The primary source [of funding] for developers is the tax credit,” said John M. Ginocchi, vice president of development for TREK Development Group, which specializes in developing affordable housing in the Pittsburgh area.

In Pennsylvania, most federal housing tax credits go through the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency, a state-affiliated agency. In 2016, PHFA allotted more than $40.3 million in tax credits to pay for 39 developments with affordable housing units in Pennsylvania. About $4.5 million worth of credits went to four developments in Pittsburgh to add 164 affordable housing units.

“The process is highly competitive,” Ginocchi said.

To show how it works, Ginocchi explained the process behind the Brew House Artist Lofts in the South Side. The building itself once housed the operation of the Duquesne Brewery, which closed in the 1970s. A ragtag group of artists began squatting there, playing a perpetual cat-and-mouse game with police until the 1990s when the group became official. They founded a nonprofit, the Brew House Association, which bought the building from the city for $35,000 in 1991, brought it up to code and began living there.

By the mid 2000s, the roof was leaking and repairs exceeded what a gang of visual artists could afford. The South Side Flats had gone from a rusted-out, post-industrial landscape to a happening nightlife district, but the Brew House Association resisted the urge to cash in and sell to a market-rate developer. They wanted to keep artists in the neighborhood and approached TREK about redeveloping the property.

TREK sent a proposal to PHFA, which had federal tax credits to dole out across the state. PHFA approved it, partially because TREK got state Historic Preservation Tax Credits to pay for some of the project. While fixing up a century-old brew house is “a unique situation,” said Ginocchi, “most developers seek funding from multiple sources.”

Developers sell the tax credits they are awarded to banks and large corporations. In the case of the Brew House, TREK received credits good for $1.2 million in write-offs a year for 10 years. They sold them to a syndicate run by the Royal Bank of Canada, which paid less than the total value of the credits to TREK.

Those funds did not pay for the whole renovation. TREK got some “traditional funding” through a bank. Mixing monetary sources meant TREK could split up the apartments between income-restricted units and ones sold at the market rate. The Brew House, which opened last year, offers apartments for rents ranging from $668 to $961 to people with incomes capped at $29,000, according to its website. Artists are given preference. There are also apartments available to anyone for rents ranging from $800 to $2,510.

Those 48 units have to be cost-controlled for 30 years, even if TREK sells the building. The rent of the market-rate unit can be raised with the renewal of any lease. That flexibility helps insure TREK will be able to pay the mortgage it took out to complete the building, Ginocchi said.

So everyone gets something they want: Low-earning artists can stay in the gentrified South Side. The Royal Bank of Canada and their partners get a tax break. TREK gets a profitable building, with some adjustability to keep it that way.

But Ginocchi said: “You have to be interested in more than money to do this. You can’t just walk into PHFA and ask for money. You have to some social benefit. It’s harder than traditional development in a lot of ways. There is a mission to what we do.”

What happens when housing covenants expire?

A housing covenant is a contract to keep involved units at a specific cost for a certain period of time.

The expiring covenants will affect 37 developments. Most will impact tenants in predominantly black neighborhoods: Eight are in Homewood, seven in the Hill District and four are in East Liberty. The largest buildings with looming expirations are the Towne North Apartments in the North Hills, Bellefield Dwellings in North Oakland, Carson Towers in the South Side, and the Kelly-Hamilton building in Homewood.

“Unless there is a way to keep the private party invested, those go back to the owner who can do whatever they want with them,” said Mabel. “So far, though, transitioning to market-rate apartments has been the exception, not the rule.”

How might affordable housing be funded in the future?

In December, the Pittsburgh City Council voted to create an affordable housing trust fund with the goal of raising $10 million annually for the construction and rehabilitation of low-income housing, plus assistance paying rent. Except it’s unknown where that money would come from. Peduto issued executive actions last week, requesting city agencies shore up resources and come up with ideas to expand and preserve affordable housing.

According to Acklin, Peduto “expressed support for an increase in realty transfer tax to invest in affordable housing and early childhood education.” This means when people or companies buy property in Pittsburgh, a tax will go to affordable housing.

The method makes sense because it would be “tied to an activity that causes an issue with affordability,” said Acklin. “When you have a high number of transfers, it indicates you have a hot market.”

The Realtors Association of Metropolitan Pittsburgh opposes this plan. “What we would prefer is for the city to liquidate its own inventory,” said John Petrack, executive vice president. The city has about 20,000 abandoned pieces of real estate. Petrack said the city should fix them up, sell or rent them with affordability stipulations and put them on the tax rolls.

Ray Gastil, director of city planning, said the city would need to do an inventory to see how many of those houses are worth the cost of repair.

Acklin said the city has made efforts to rehabilitate and make use of its abandoned properties but the complexities of deeds and ownership often complicate such efforts.

Any solution depends on the continued use of tax credits coming from the federal government, he said. “Those underline every effort we make.”

He added the policy makers within the city government are nervous about changes during the Donald Trump presidency. “Developers sell those tax credits on the open market,” said Acklin. “The Trump administration has signaled tax cuts for corporations, which would make the [tax credits] less valuable, in effect creating gaps in affordable housing.”

Clarification (1 p.m. 2/23/2017): The story previously only mentioned that the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development administered Low-Income Housing Tax Credits and other housing assistance; however, the Internal Revenue Service is also involved in the allocation of assistance.

Nick Keppler is a Pittsburgh-based freelance writer who has written for Mental Floss, Vice, Nerve and the Village Voice. Reach him at nickkeppler@yahoo.com.

PublicSource Interactives and Design Editor Natasha Khan produced the graphics for this story.

In the past Pittsburgh has always lagged behind national trends including housing. The real question is, whether the salaries being paid in Pittsburgh today support the housing boom we are presently experiencing. One top realtor in western Pennsylvania stated live during a local news story he believe that present wages and salaries in Pittsburgh do not support the boom we are experiencing in housing and he predicted a bust in a couple of years. Then what?

For more than you ever probably wanted to know about housing cost burden and the 30% standard, look to the Census Bureau document referred to in that article. I found it interesting that among the states where tenants paid the highest percent on rents – in addition to the

predictable California and New York – is Mississippi and Louisiana!

https://www.census.gov/housing/census/publications/who-can-afford.pdf

Interesting. Fortune magazine recently made the argument that the 30 percent rule of thumb is unrealistic. I know, Fortune magazine, but still … if the poverty rate and minimum wage are suspect because they’re based on outdated measurements, then perhaps the housing affordability calculation can be revisited. http://fortune.com/2015/08/04/housing-30-percent-rule/

The federal standard for home affordability has been 30% of adjusted gross income for all housing related expenses. That’s why banks typically qualify a family for a mortgage based on 28% of adjusted gross income (leaving taxes, insurance and utilities to make up the other 2% or so). If you do the math, a $64k annual salary is $5,333 per month. 30% of that is $1,600.

I think they’re talking about before-tax income. So there would be significantly less than $40k left over.

I don’t understand how one would need a $64,000 annual income to “reasonably afford” a $19,200 annual rental. Seems like very creative estimating. Even a $2,000 a month rent ($24,000 for the year) as opposed to the $1,600 per month figured in the article/report, would leave $40,000 for all other expenses.